|

This is a Temporary Page

In 1743 a Qaraqalpaq deputation left for an audience with the Empress in Saint Petersburg, where their request for allegiance was positively

accepted and formalized in a deed of loyalty, which conveyed Russian citizenship in return for favourable trade relations and the release

of Russian captives. Henceforth the Qaraqalpaqs would pay tribute to Russia rather than the Qazaqs.

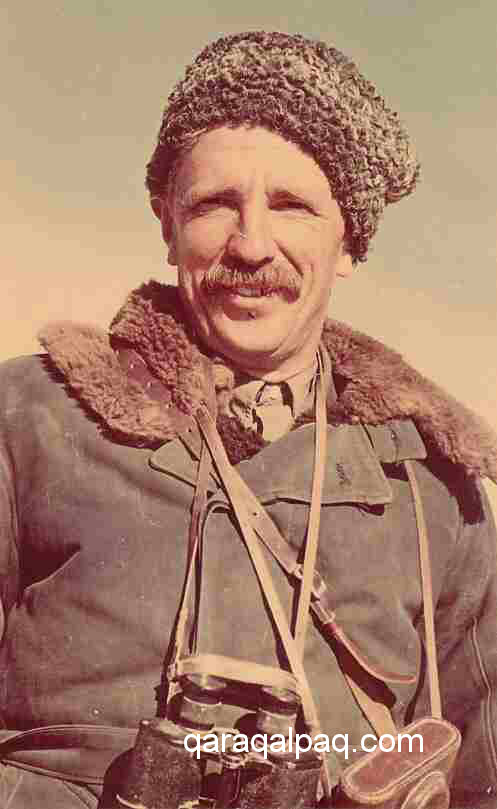

The envoy Maman biy, who returned from Saint Petersburg in 1743

with a declaration of Russian citizenship for the Lower Qaraqalpaqs.

Painted by Barlıqbay Aytmuratov. From the collection of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis.

On hearing this news Abu'l Khayr became furious and attacked the "lower" Qaraqalpaqs for their disloyalty, plundering and destroying their camps

and driving off their cattle. Having failed to gain Russian support for his ambition to rule over all the Qazaq Hordes, Abu'l Khayr turned against

the Russians and began attacking their frontier settlements. This violence encouraged the Qaraqalpaqs to migrate further to the south-west, into

the region between the Quwan Darya and Jan'a Darya and into the eastern part of the Amu Darya delta. Ironically, their Russian citizenship seems

to have offered them scant protection and as they moved to the south so the new-found relationship with Russia disintegrated.

In 1748 the Sultan of the Middle Horde hatched a plot with dissidents within the Lesser Horde and Abu'l Khayr was killed. The Lesser Horde became

divided into a minority group led by Abu'l Khayr's son, Nur Ali, supported by Russia, and a majority anti-Russian group led by the dissidents. The

latter frequently attacked the Qaraqalpaqs, no longer just to regain domination over them but to take their land, making up for shortages of grazing

land in the north. The "lower" Qaraqalpaqs were now wintering close to the reed beds along the Aral Sea and had built earthen fortresses to defend

themselves against the Qazaq raids. In the summers they were venturing far and wide to trade their livestock, even reaching as far as Khiva.

In 1762 some 20,000 Qazaqs embarked on a massive raid on the northern Qaraqalpaq territories, forcing the Qaraqalpaqs yet further south. Life

in the northern Syr Darya delta had become intolerable and the 1760s saw a major migration of Qaraqalpaqs into the lower Jan'a Darya, which became

the densest region of Qaraqalpaq settlement. But more and more Qaraqalpaqs were moving into the northern Amu Darya delta, especially along the

banks of the Ko'k o'zek. Here in Khorezm they found natural allies amongst the dissident Uzbeks who, having resisted rule by Khiva, had no desire

to see an invasion by Qazaqs. Together the Qaraqalpaqs and the Aral Uzbeks were able to repulse further incursions by the Qazaqs. Finally in

1759 the Chinese defeated the Jungar Khanate and annexed it to form Xinkiang, thereby removing some of the pressure on the Syr Darya Qazaqs from

the east.

|

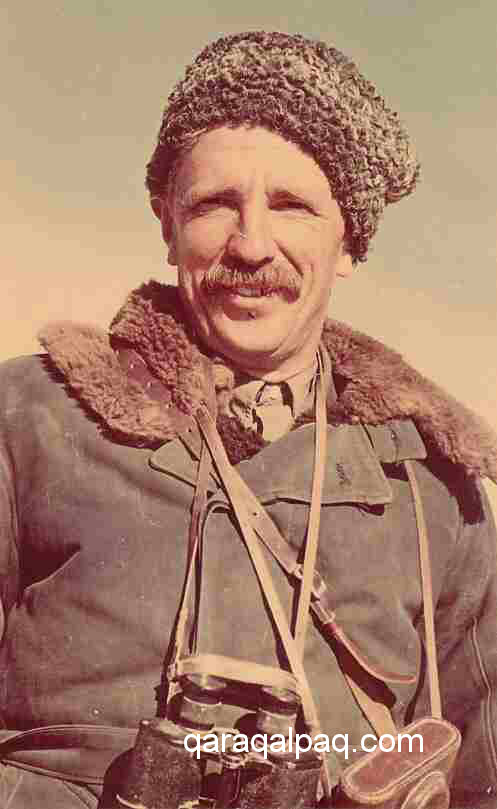

Sergey Pavlovich Tolstov, the founder and head of the Khorezm Archaeological-Ethnographical Expedition.

The 18th century Qaraqalpaq irrigation network on the Jan'a Darya was investigated by members of that Expedition

under the leadership of B. V. Andrianov and Ya. G. Gulymov. Photo courtesy of the Regional Studies Museum, No'kis.

It seems that the Qaraqalpaqs were not yet politically unified at this stage, since the Khiva chronicles make no mention of a ruling Khan. Each

clan was lead by its own separate biy, normally a wealthy land and cattle owner. Historical legends suggest the On To'rt Urıw

arıs was led by a biy called Orınbay from the Man'g'ıt tribe and that a biy called Esengeld biy

was influential amongst the Qon'ırat arıs.

The Qaraqalpaq fortress of Orınbay Qala on the lower Jan'a Darya.

Illustration courtesy of the Khorezm Archaeological and Ethnographical Expedition.

Wealthy land-owning Muslim priests and shamans called iyshans,

xojas or shayıqs also exercised considerable influence within the tribes. The constant threat of invasion influenced the type

of Qaraqalpaq settlement. Qaraqalpaqs now settled in groups, with the whole tribal union sometimes living together – especially during the winter

when the possibility that their enemies could cross the frozen rivers meant that the risk of attack was greater. Each group or awıl

built a fortress or qala consisting of an outer earthern rampart within which all the yurts and cattle could shelter. The clay farmhouse

of the head of the awıl was usually placed inside, at the centre of the fort.

A map of the Russian Empire dated 1793 showing Lower Qaraqalpaqs living on the north-east shores of the Aral Sea.

The Qaraqalpaqs developed a complex irrigation network in the Jan'a Darya oasis and maintained their mixed pastoral-agricultural lifestyle. The full

extent of this vast irrigation system was only discovered in 1946 when Tolstov organized the first aerial survey of the Syrdarya delta. Tolstov

described it as a "majestic monument" to the work of the ancestors of the Qaraqalpaqs. The archaeologist Andrianov was even more impressed with

the sophistication and construction of the irrigation system when he recorded it on the ground in 1957. Tolstov finally conducted a detailed survey

to record the remains of the Qaraqalpaq irrigation system in the Syr Darya delta during the 1960s.

Return to top of page

Home Page

|