Qaraqalpaq Jewellery

|

Qaraqalpaq Jewellery

|

|

ContentsIntroductionSa'wkele Plait Decorations Nose-Rings Earrings Necklaces Ayshıq O'n'irshe Tu'yme Ha'ykel Tumar and Tumarsha Giltshalg'ısh O'n'irmonshaq Bracelets Rings Qaraqalpaq Jewellers Materials and Techniques Where to see Qaraqalpaq Jewellery Pronunciation of Qaraqalpaq Terms References IntroductionJewellery, especially silver jewellery, formed an essential part of a Qaraqalpaq woman's costume. It was worn by all levels of society. Rich people were able to commission a full set from a jeweller or zerger. Less wealthy people could only afford to have a limited amount and it would be of poorer quality material and roughly made. Jewellers were able to produce and sell such poorly made items because of their perceived protective properties. Some jewellery items, such as the tumar, were believed to be able to drive away the evil eye.

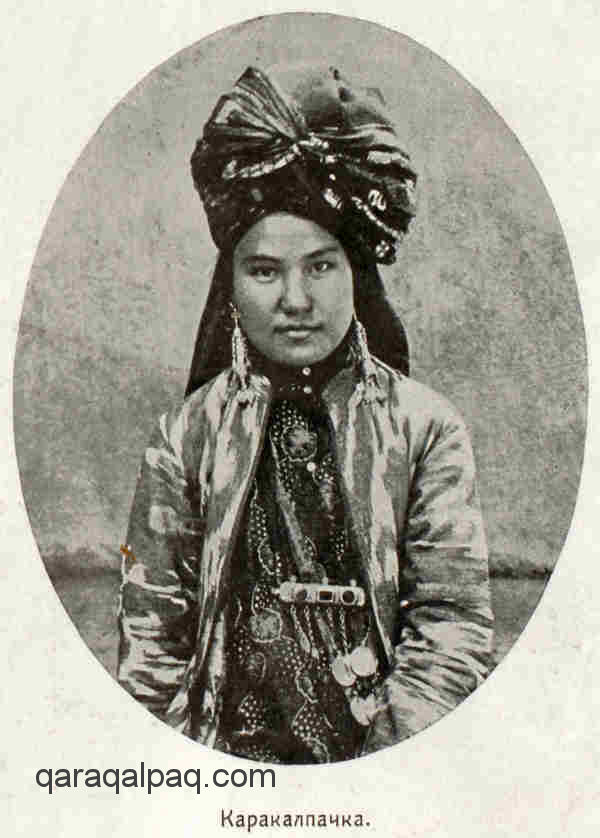

Traditional costume of a Qaraqalpaq bride, with a'rebek nose-ring, soyaw sırg'a earrings and a dramatic

|

|

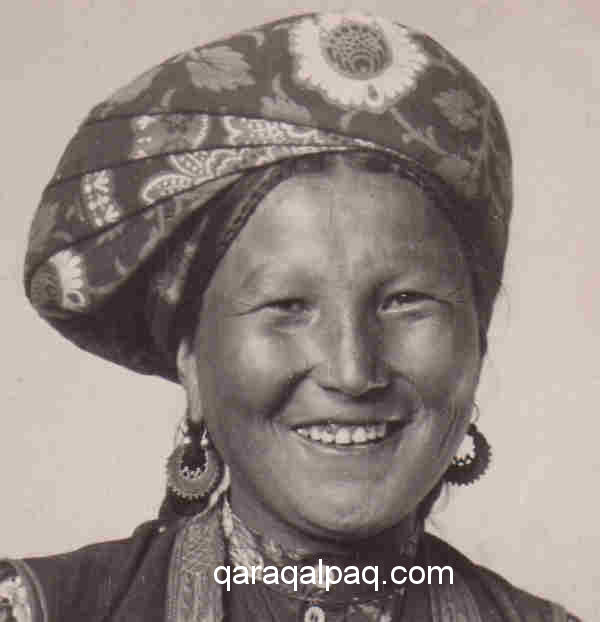

Photographic evidence is also limited. The Turkestanskiy Albom, a fantastic collection of ethnographic photographs compiled on the orders of General

Kauffman, was completed just before the fall of Khiva and the annexation of the Amu Darya Otdel. Consequently it excluded all of the people

living in the lower Amu Darya. The photographs taken by Melkov in the late 1920s tend to show women at work and therefore not dressed in their

finery or wearing full jewellery. Some of the photographs held in the archive of the Savitsky Museum probably date back to the 1930s and look very

staged. During the Soviet era women were mainly photographed for political purposes, working for the collective farm in the cotton fields.

One final problem concerns attribution. Unlike costume or yurt decorations, some items of Qaraqalpaq jewellery are similar to Qazaq, Turkmen, or

Uzbek items. It is often difficult to assign such items to their ethnic category once they have been removed from their context and have lost their

provenance. They tend to be labelled with the catch-all "Central Asian" or, more disturbingly, attributed to whichever group the seller feels

the buyer is most interested in! Place of purchase is no guarantee of origin as we have seen Qaraqalpaq jewellery for sale in locations ranging

from Bukhara to Ashgabat and from Istanbul to Kuala Lumpur.

Sa'wkele

During the 19th century the sa'wkele was the pinnacle of the Qaraqalpaq jeweller's craft - the most exclusive and expensive creation imaginable.

However the sa'wkele is such a rare and important item of Qaraqalpaq material culture that we have devoted three separate web pages to its

description and history. Please click here for more details.

Plait Decorations

The earliest reference that we have to Qaraqalpaq plait decorations is from Ivan Muravin, the surveyor of the diplomatic expedition to the Aral region

led by Lieutenant Gladyshev in 1740:

"Their daughters, like the Kirgis [Qazaqs], braid their hair into two plaits to the shoulders, until the hair grows,Unmarried girls generally plaited their hair into four small braids. Their hairstyle differed from that of the Khorezm Uzbeks and Qazaqs in that they had two small plaits at the front of their temples in addition to the main plaits descending down their back. These temple plaits were in turn made of two smaller plaits wound together. They were known as tulımshaq and were worn from the age of about 11 to 12 years old.

and afterwards wind it together with the white coarse calico, made for the purpose, to the ground".

|

|

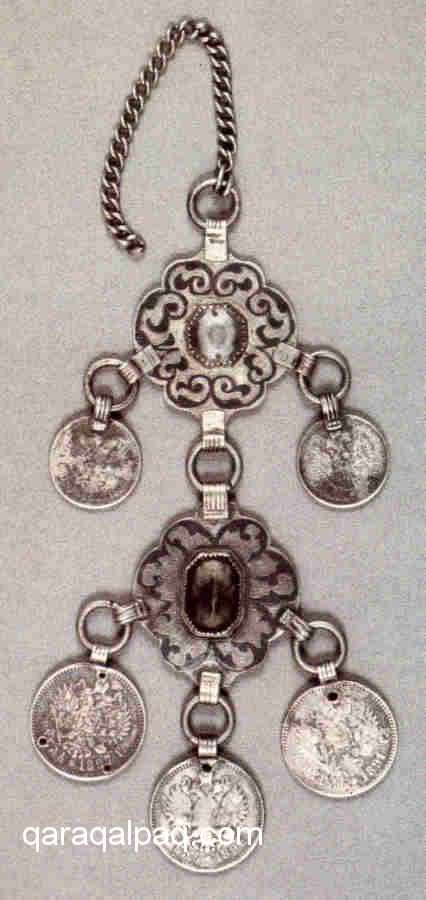

On the left is a sholpı from the Regional Studies Museum in No'kis utilizing coins including an 1895 rouble. On the right is a

19th century sholpı from North Kazakhstan. This is in the collection of the Abylkhan Kasteev State Museum of Arts of the Republic of

Kazakhstan.

Nose-Rings

The Qaraqalpaq term for a nose-ring is a'rebek. A'rebek were one of the few items of Qaraqalpaq jewellery that were usually

made of gold. M. N. Galkin, a diplomatic official with the Orenburg Governor-General, travelled from Orenburg to Khiva in 1858.

He camped near Aybugir Bay on the way to Qon'ırat:

"The coastal inhabitants are Karakalpaks. Their facial features are more regular, and more beautiful than the Kirghiz [Qazaqs]. Some Karakalpak women wear a ring in the nostrils."Riza Quli Mirza saw Qaraqalpaq women wearing nose-rings in Shımbay in 1874:

"Sometimes they wear the ring, passed through one of the nostrils, which disfigures the face terribly."A'rebek were very common in the northern regions of Qaraqalpaqstan at the end of the 19th century. However by the end of the 1930s women had stopped wearing them even in the rural areas. Morozova writes that in 1948 women had started to wear their a'rebek as earrings – they simply ordered another one to make a pair. Conducting research in the 1970s O'temisov found that they were still kept in many homes but were no longer worn.

|

|

It is interesting that elsewhere in Central Asia nose-rings were only worn by the Uzbeks and the Tajiks but not by the Qazaqs, Kyrgyz, or other Turkic peoples of East Turkestan. However nose-rings were common among the Tatars or Eastern Europe such as the Noghay and the Astrakhan Tatars, as recorded by Johann Georgi in 1776:

"Besides rings and earrings, some of the Nogay women wear a golden ring in the cartilage of the nose so large that it reaches to the lips; and even some of the Tatar women in the city of Astrakhan follow this custom. The women of Kundorov wear this ring in one of their nostrils."

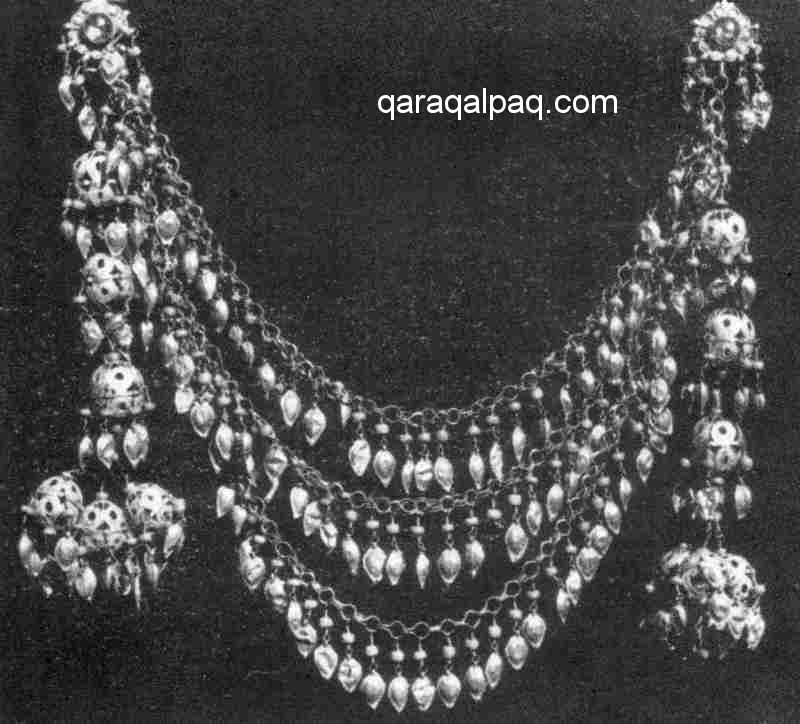

"... wear silver earrings in their ears, very large but, like the bracelets, of very rough work and Russian silver coins frequently serve as pendants to them. Sometimes the earrings are so heavy that, besides the opening in the ear, they are supported by a thread which circles around the entire ear."At the turn of the 19th century there were many different types of sırg'a, the most impressive and ancient of which was probably the halqaplı sırg'a. This decoration consisted of a pair of earrings connected to each other by a chain or necklace from which were suspended numerous pendants. The description halqaplı seems to mean circular and refers to the necklace component. There are various spellings of this including halqalı, qalqalı, and halqanlı. We have chosen to use that given in the Qaraqalpaq Glossary of Artistic Crafts.

|

Other examples incorporate coral beads on the pendants.

The Qaraqalpaq halqaplı sırg'a is remarkably similar to an item of Khorezmian Uzbek jewellery known as a shokila.

The main difference seems to be that the necklace of the shokila is connected to two temple pendants, rather than two earrings.

|

The halqaplı sırg'a was worn by a girl from the age of 12 until her wedding, and then for the following three days afterwards.

|

On the fourth day of marriage it was removed. After the halqa or chain part had been removed the newly-wed bride continued to wear the earrings

which then became known as either soyaw sırg'a or baldaqlı sırg'a.

|

|

Sobıqlı sırg'a were a simpler version of the soyaw sırg'a with the same basic shape of a small cone or

droplet but without any pendants. The word sobıq means bean.

Marjanlı sırg'a are also somewhat similar but have the addition of small coral or marjan beads.

|

Bu'rshikli sırg'a were small earrings, generally of silver, in the shape of a half-moon. The pattern was achieved

by means of granulation. Esbergenov suggests that women began to wear these at the age when they were capable of bearing a child as the

moon shape is linked to fertility. He argues that the figures incorporated on the inner curved edge of some of these earrings may

be anthropomorphic.

|

|

Jalpaq sırg'a (flat earrings) came in various sizes. They were often made of tilla' - an alloy of gold and silver.

|

The final type of earrings are the shıyırtpaq sırg'a. These are long and flat and generally have three concentric circles.

They were worn by elderly women.

|

|

Although the two sets of jewellery shown above look very similar they are used for different purposes. The Qaraqalpaqs wore them in their ears

but the Qazaqs wore them at the temples, either attached to their hair or to some form of headwear.

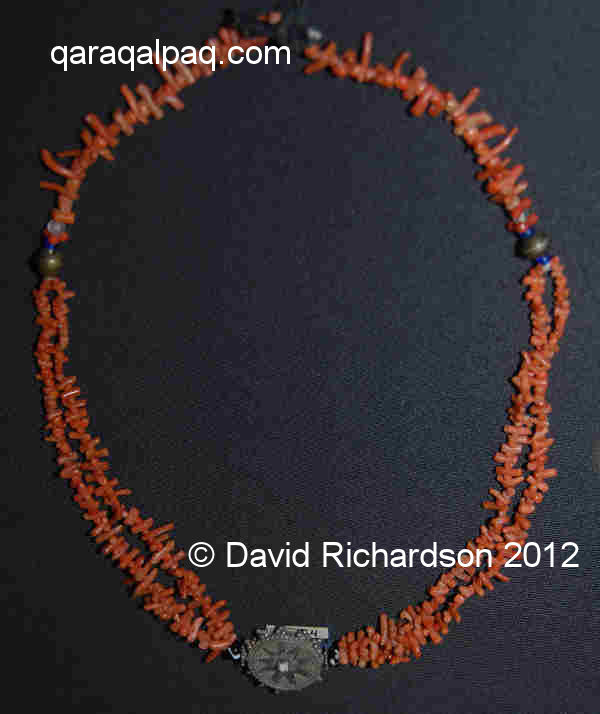

Necklaces

Very few Qaraqalpaq women had a necklace within their collection of jewellery. Necklaces were generally seen to be an Uzbek fashion.

Women questioned by Morozova said that in the past Qaraqalpaq women did not wear silver necklaces. However women in Shımbay and in the

southern regions of Qaraqalpaqstan bought necklaces in the Khivan style made of silver and gilded chains with turquoise and various pendants.

In some rural areas necklaces of coins known as xan-ten'ge or necklaces of coral could be seen.

|

|

Morozova recorded how in the decade following the Great Patriotic War a new type of necklace had become fashionable among Qaraqalpaq women.

Called a tamaq-qatar it was shaped like a dog collar and patterned with black and white glass beads threaded

onto rows of thick silk. It seems to have been adopted from the Uzbek women living north of Khanki in the northern part of the Khorezm oasis.

Ayshıq

The word ay means moon in Qaraqalpaq and often features in the traditional names of Qaraqalpaqs, especially those of females (Aygu'l,

Ayjamal, Aynagu'l, etc.). Cult beliefs linked the moon with fertility so it is perhaps not surprising to find a piece of female jewellery

named after the moon. Ayshıq were generally made of silver, a metal traditionally associated with the moon, and often had a

central mount of carnelian or coloured glass. They are usually 7 to 9 centimetres in diameter. They were worn either as a brooch or as the

neck fastening for a dress collar.

|

The most important piece of jewellery for a bride was the ha'ykel – see below. However, if her family was unable to afford this

then she wore an ayshıq and a shartu'yme. If they could not afford both, then she wore just an ayshıq.

O'n'irshe

The Qaraqalpaq o'n'irshe was basically an embroidered textile breastplate made from the red woollen felted cloth known as

qızıl ushıga. Sometimes the design included borders of qara ushıga and all of the outside edges

were finished with raspberry red jiyek. A variety of decorative adornments were sewn onto this breastplate, such as metal platelets,

coins, several types of tu'yme and the giltshalg'ısh. It was worn by unmarried girls of marriageable age.

|

The o'n'irshe is actually a piece of clothing and we intend to devote a separate webpage to it at a later stage. However it is

necessary to include this short description here in order to place the use of certain other jewellery items in their context.

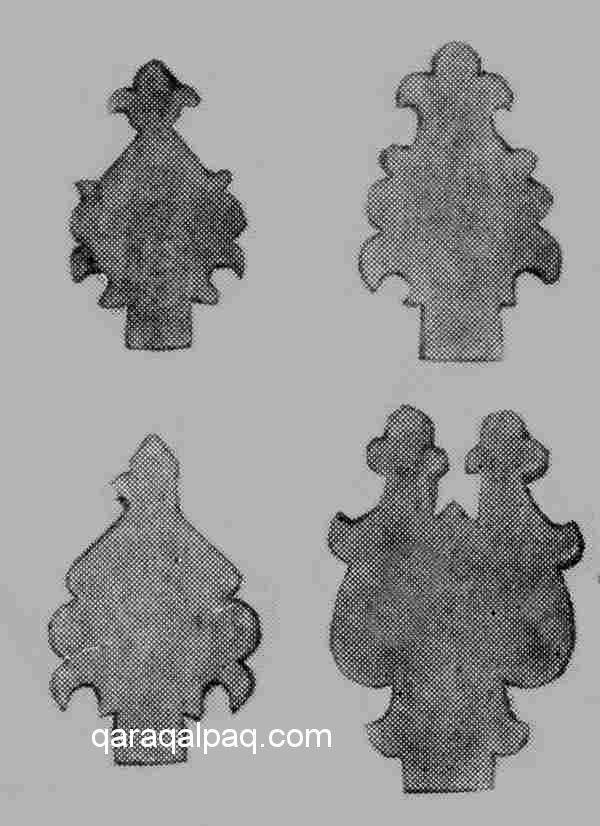

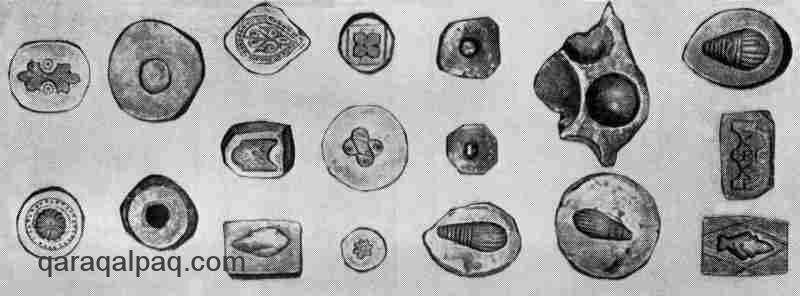

Tu'yme

Tu'yme are brooch-like items of jewellery frequently incorporated into breast decorations.

There are 3 main types of tu'yme:

|

|

|

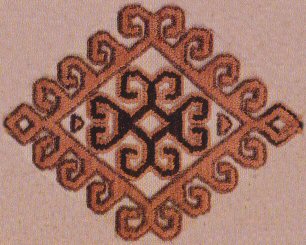

Morozova recorded that:

"In some breastplates the shape of the 'boka–tuyme' was absolutely identical to the shape of the carpet medallion called 'Karakalpak-nuska' – 'the Karakalpak pattern' by Fergana carpet makers."We have been unable to find any examples of baqa tu'yme that resemble the 'Karakalpak nuska' and wonder if there may have been some confusion with the shartu'yme which does have some similarities to it.

|

It is interesting that Qoraz Tilewbayev's moulds are for baqa tu'yme, which were supposedly preferred by by the On To'rt Urıw. However he

was from the Uyg'ır tribe, part of the Qon'ırat arıs who supposedly favoured the jumalaq tu'yme.

|

There remains some confusion regarding the manner in which shartu'yme were worn. Esbergenov believes that when a family could not

afford a ha'ykel the shartu'yme was worn as a less expensive substitute. Consequently the shartu'yme and

the ha'ykel were never worn together. However Ag'ınbay Allamuratov wrote that two shartu'yme were sometimes

fastened to the bottom edges of the ha'ykel.

Aygu'l Pirnazarova, the Curator of Costume and Jewellery at the Savitsky Museum, recalls a man who used to collect material for the museum.

He discovered a ha'ykel with two shartu'yme attached to the sides of its bottom edge, now held in the reserve collection. He

emphasized that it would be a great sin to separate this ensemble. However this seems to be a unique example and one in

which the shartu'yme appear to have been added later in a rather amateurish fashion. It remains the only solid proof

that shartu'yme were worn with the ha'ykel. Nevertheless Aygu'l adds that she has shown this combination to many local

people and none has so far indicated that the arrangement was incorrect.

|

Perhaps the truth lies somewhere in between. Allamuratov was very knowledgeable and it would be foolish to dismiss his comments. It is likely that

a small minority of very wealthy Qaraqalpaqs could embellish a ha'ykel with two additional shartu'yme for an elaborate wedding

display. However in the majority of cases it is likely that the shartu'yme was primarily used as an independent item of jewellery.

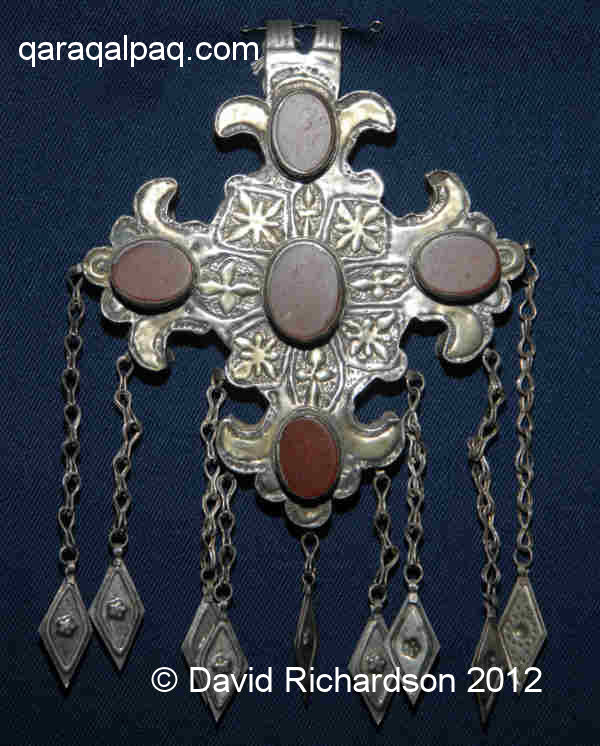

One wonders whether the Qaraqalpaq shartu'yme, like the ha'ykel breast decoration discussed below, has connections to the

Volga region of Russia. It is interesting that the Chuvash also have a breast decoration known as a shulgeme. Another avenue

we have yet to explore is whether there is any connection with the Christian cross - the shape of the shartu'yme has similarities

to that of the medieval four-ended baptismal cross used by members of the Russian Orthodox church.

Ha'ykel

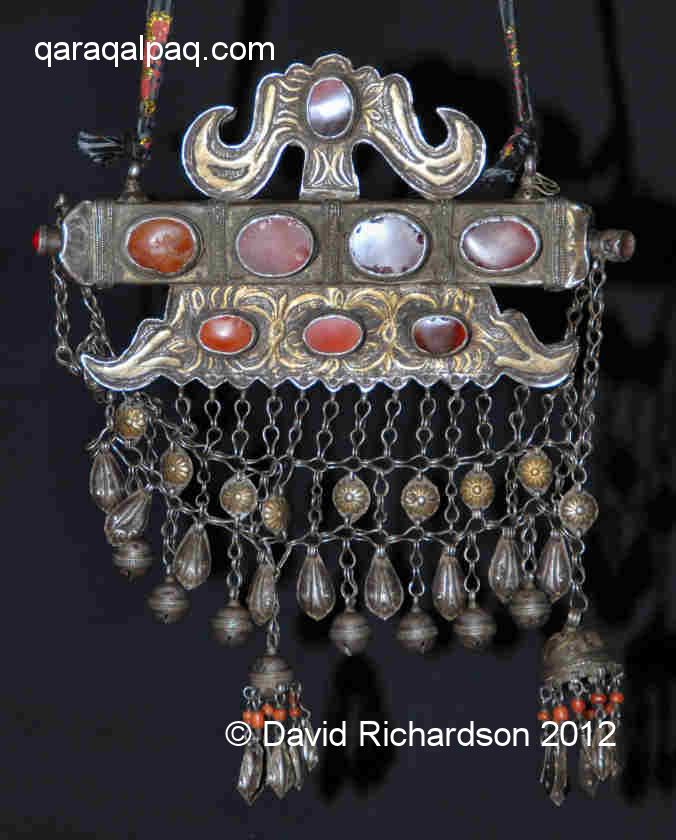

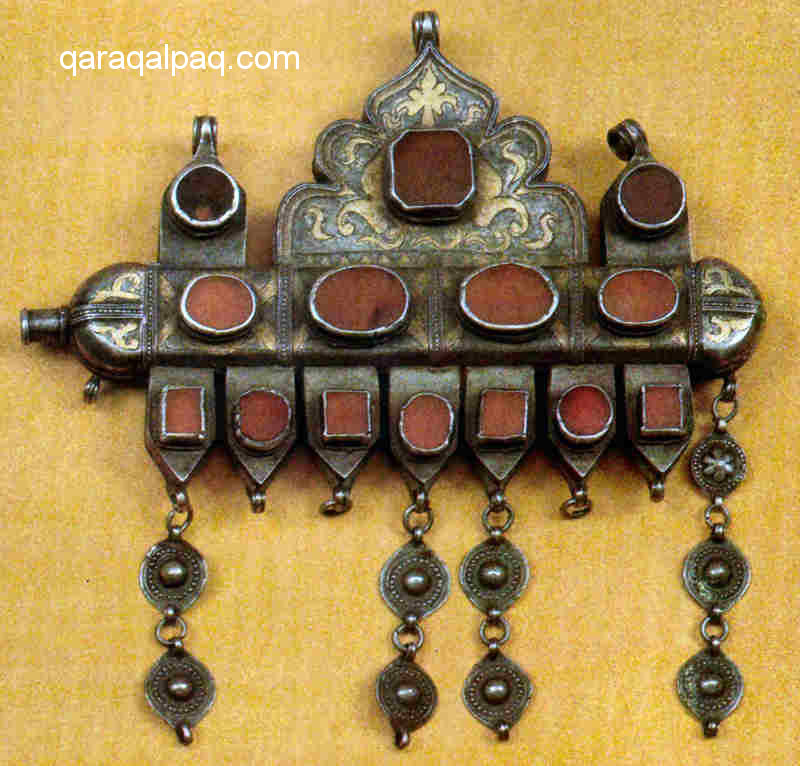

Apart from the sa'wkele, the ha'ykel is probably the most impressive single item of Qaraqalpaq jewellery. It is a breast

decoration, generally of silver and sometimes gilded, with carnelian or coloured glass inserts.

|

From the age of 12 to 14 upwards, young girls wore the qız ha'ykel which was much simpler than the adult version but based on

the same layout. It was also smaller with the width of the eight examples in the Savitsky reserve collection ranging from

10½ to 13½ centimetres. However within the collection of the Savitsky Museum there is only one qız ha'ykel for

every 19 ha'ykel, suggesting that these were far less common. When she was ready to get married the bride-to-be passed on

her qız ha'ykel to her younger sister and her father commissioned an adult ha'ykel from a zerger.

This was the foremost item in the jewellery set of the bride.

|

The ha'ykel was put on by the bride at the very start of the wedding ceremony, when she was dressed in her own home before she moved

away to the house of the groom. She continued to wear the ha'ykel for festivals and family celebrations up to the birth of her

first child and sometimes up to the age of 40. It was no longer worn once she had passed the age of childbearing.

Ha'ykels vary enormously in shape and design and it is difficult to sort them into definitive categories. At the end of the day it is hard

to improve on the description and typology of the ha'ykel given by the Qaraqalpaq researcher Ag'ınbay Allamuratov. Readers may

achieve a better understanding of his comments by referring to the following illustration:

|

|

The majority of the ha'ykels that we have seen are of this horned style. An indication of the cost of the ha'ykel can be gained

from the example shown above. Sadegu'l from the Qarasıraq clan was born in 1895 in Qarasıyraq awıl in the Kegeyli

region. It is believed that she was married sometime between 1910 and 1920. For her wedding her father commissioned a ha'ykel the price

of which was one cow.

|

Allamuratov did not explain why the bull should have been an important component part of some ha'ykels and not of others. Nor did he

try to link the ha'ykel with horns to any specific clan-tribal group.

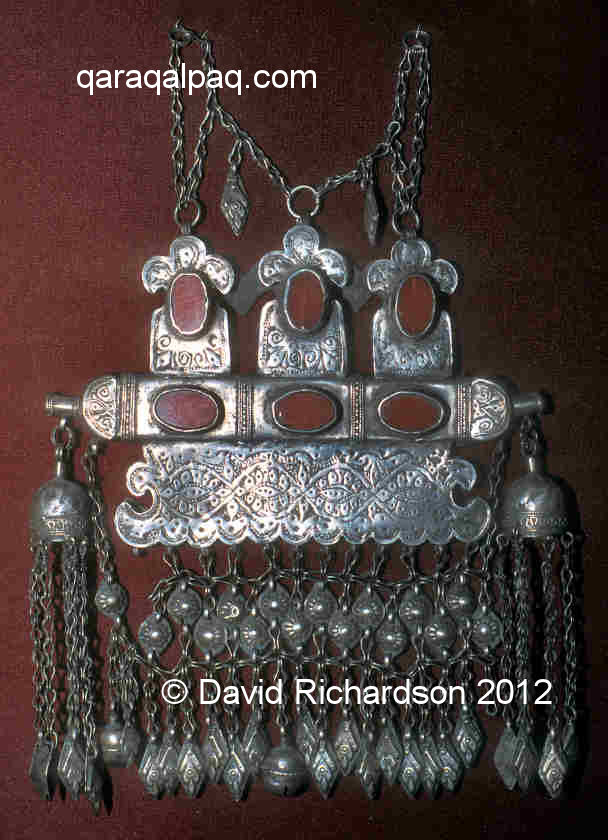

Now we will review the two types of ha'ykel decorated with trefoils:

|

Savitsky thought that some characteristics of this type of ha'ykel were tribe-specific. The example above was believed

to be typical of the Mu'yten tribe, cattle-breeders who formerly inhabited the southern shores and islands of the Aral Sea. The top ends of

the ha'ykel bas, which Allamuratov interpreted as trefoils, were interpreted by Savitsky as stylized ram's heads. To complicate matters

further, an elderly Qaraqalpaq man informed the Savitsky Museum that his grandfather (a Mu'yten) had told him that they represented three

anthropomorphic figures sitting down. Alas we are dealing with conflicting opinions and not facts.

|

The ha'ykel was definitely viewed as amuletic, protecting the wearer from misfortune and the evil eye. Items found inside some ha'ykels

included very old pieces of textile, threads with knots, salt, and paper inscribed with prayers.

Not all ha'ykels fit neatly into Allamuratov's four design types. The following examples are like a cross between types III and IV, with a

single narrowing ha'ykel bas bearing three clusters of trefoils. We regard it as a type V design:

|

The example of the narrowing trefoil design given above has a very bold pattern engraved on the face. The addition of two more decorations on the

chain is unusual. It has some similarities to the ha'ykel shown by Johannes Kalter in Heirs to the Silk Road.

The second type V ha'ykel has another boldly decorated face. In this case the trefoils are more horn-like, the two lateral trefoils being

partly integrated within the ha'ykel bas.

|

One further feature of ha'ykels is the variation in their quality of manufacture, ranging from crude to sophisticated.

|

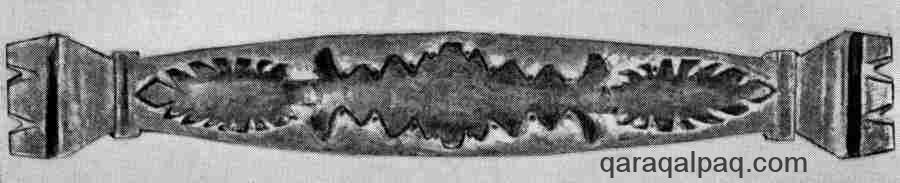

Ha'ykels were made using stamps and moulds.

|

These moulds belonged to the hereditary master-jeweller Qoraz Tilewbayev (1848-1919) and were found in the State farm named after A. Musaev, in

the Shomanay region, in 1974.

Some have suggested that the base of this style of ha'ykel is representative of the crenulated walls of a qala.

|

Ha'ykel-like pectoral decorations are not restricted to the Qaraqalpaqs. Allamuratov observed that similar items were worn by the

Turkmen, Uzbeks, and Tajiks of Central Asia and by the Bashkirs, Udmurts, Mordvin, and Chuvash of the Volga region of Russia. For example the

Bashkirs wore a semi-oval breast decoration decorated with silver plates, carnelians and small bells. It was called a hakel.

Although the Qazaqs wore the small tu'marsha triangular amulets and the larger composite boi tu'mar, both differed significantly

from the Qaraqalpaq ha'ykel.

The distribution of such decorative hangings among the peoples of the Volga and their absence among the Qazaqs, Kyrgyz, and Tatars of Eastern

Turkestan might indicate a point of origin in the Volga region – as with the sa'wkele headdress.

Within Central Asia only the Turkmen seem to have an analogous item of jewellery, found among the Tekke and Ersari. This has a very similar

shape to the Qaraqalpaq ha'ykel. Does this indicate that it was influenced by the Qaraqalpaqs?

|

Possibly not, since the Turkmen nomenclature is quite different. Turkmen refer to their ha'ykel-like decoration as a tumar, whereas

the Qaraqalpaqs use the term tumar to denote the middle horizontal tube of the ha'ykel. The item known as a kheykel' by

the Turkmen is very different. It has the shape of a small box, is often of leather, and is trimmed with silver platelets.

|

According to Kate Fitz Gibbon these 'leather envelopes' were used by old women. She believes they contained prayers or keys rather than a

copy of the Qu'ran as has been suggested by some writers.

Tumar and Tumarsha

In Qaraqalpaq jewellery a tumar is a small plain hollow silver tube. If it has inserts of stones or coloured glass it is called

a tumarsha. Larger examples were worn on chains around the neck while smaller ones were sewn onto clothing. They were worn by

children and young women. They were believed to have amuletic properties and were sewn onto the back of children’s clothing. Leaves, plants,

and a piece of paper with a prayer written onto it were packed inside the tube of the tumar as 'protection'.

|

|

Researchers in 1948 found that the style in women's jewellery was changing rapidly and that by the end of the 1930s the tumar amulets had

become much smaller. The fashion was for the new gilded tumars with turquoise inserts.

The word tumar is now also used to apply to a piece of textile made into a bag, with various protective elements inside it such as

bread, salt, and onion skin.

|

The Tekke tumar shown above seems to be something of a halfway house between a tumar and a ha'ykel.

|

Giltshalg'ısh

This is a pendant for a key (gilt) and is occasionally referred to as an anshıq. It has the shape of a double loop,

interpreted by Alieva as a stylized female figure, and usually has a stone or coloured glass insert. The examples that we have seen range

from 6 to 9 centimetres in height. The metal used varies, some are of silver and some are bronze.

|

|

For everyday wear the giltshalg'ısh was hung around the neck and then the keys were suspended from it.

|

However on festive occasions the giltshalg'ısh was sewn onto the tapered end of the o'n'irshe and an o'n'irmonshaq

was hung from it. See the following section.

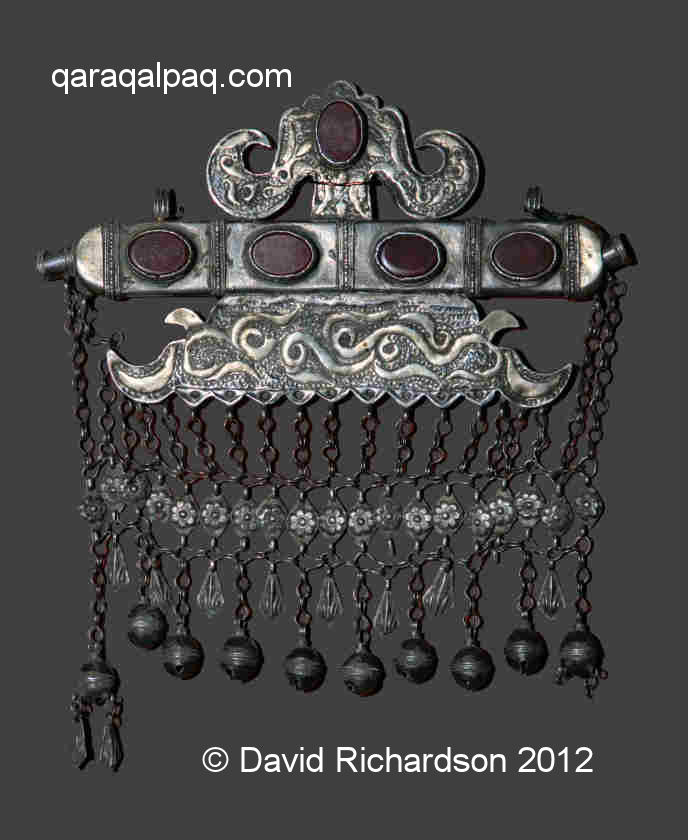

O'n'irmonshaq

As previously stated the o'n'irmonshaq was considered to be one of the essential parts of a bride's set of jewellery. It is a symbol

of motherhood, worn just below the navel. Its shape is said to resemble the cupola of mosques and mazars, but this may be a recent

interpretation. The top section is generally engraved and often gilded. Some examples are inset with small stones such as turquoise and

coral. Below the hemisphere is a circle with an ornamental fringe (shashaq) of dozens of small lengths of chain,

each terminating in a small decoration such as a stamped leaf or a bell. An o'n'irmonshaq from the Savitsky Museum has a metal

toothpick attached to one of the chains.

|

The o'n'irmonshaq was hung from the giltshalg'ısh which in turn was stitched to the base of the o'n'irshe.

Only the top part of the o'n'irshe was attached to the clothing. Morozova explains how

this meant that the o'n'irmonshaq moved freely, making a pleasant sound which was reflected in a folk song about 'ringing girls'.

|

O'n'irmonshaq were a costly item of jewellery. Sadegu'l from the Qarasıraq clan was born in 1895 in Qarasıyraq awıl

in the Kegeyli region. It is believed that she was married sometime between 1910 and 1920. For her wedding her father commissioned

an o'n'irmonshaq the price of which was 1 cow.

|

For the wedding of a bride from a wealthy Qaraqalpaq family the o'n'irmonshaq was hung from the giltshalg'ısh and worn in

combination with the ha'ykel.

Bracelets

The Qaraqalpaq word for bracelet is bilezik. Many Qaraqalpaq bracelets have close similarities to those of the neighbouring

Qazaqs and Turkmen.

There is some confusion over which bracelets were worn by which groups. Some of the elderly informants questioned in the 1970s asserted

that bracelets were not part of the jewellery set of girls as they were a symbol of the faithfulness and honesty of wives. Describing the

role of jewellery in courtship, Zafara Alieva explains how the bride's parents gave a gift of nine items (togızlıq) to

the matchmakers. The first of these was a silver bracelet and this signified that the girl was now betrothed. She also states that the

bride first put on adornments in the shape of a ring (i.e. rings and bracelets) on her wedding day as these were symbols of matrimonial

fidelity. However, according to O'temisov, girls bracelets were narrow and were worn from the age of 12 up to marriage. It is likely that

there were strict rules in the past and that these changed over time.

|

Aygu'l Pirnazarova of the Savitsky Museum believes that these were worn by young girls. However Morozova states that they were worn by women from

rural areas.

|

|

The similarity between the Qazaq and Qaraqalpaq bracelets shown above is striking.

|

|

These bracelets were typically worn by a young married woman. The ends of these bracelets resemble a row of teeth.

"...on their hands are copper and silver bracelets with poor turquoise or jasper."The first image that we have available to us is the following photograph taken by the Swiss explorer Ella Maillart of her Qaraqalpaq companions in 1932.

|

We can see that the lady is wearing a pair of qaslı bilezik. Although there are other images of Qaraqalpaq women wearing

jewellery their arms are usually covered by the very long sleeves of their clothing and so it is impossible to see any bracelets.

Rings

The Qaraqalpaqs have several different types of rings or ju'zik which include:

|

|

According to O'temisov, one of the characteristic features of Central Asian rings were their high mounts. This was due to the fact that

they were made from wire flattened by blows from a hammer.

Qaraqalpaq Jewellers

Qaraqalpaq jewellers were known as zergers - a Turkic word derived from the Persian zar meaning gold. They mainly manufactured

women's jewellery articles, but also men's belts and silver decorations for horse saddles and tack. Some Qaraqalpaq zergers were only

involved in making jewellery but some doubled up as blacksmiths as well.

At the end of the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century there was a zerger working in almost every large village throughout the delta.

Many usually also worked in the adjacent smaller villages. Sometimes jewellers worked in their own homes and sometimes in the homes of their

customers. They were generally paid with grain or cattle, less frequently with money. Occasionally they received silver as payment,

which they presumably reused.

Some jewellers who made the more expensive goods were relatively well off, owning land and cattle, such as Oraz zerger who was listed in

the Khivan Khan's archives of 1869-1872 as owning 75 head of cattle and 106 sheep. Others could not exist on their earnings from this

trade and so were also involved with agriculture, fishing, and cattle-breeding.

|

Jewellery making was a hereditary craft in which the masters generally trained either their own son, or a close relative, or failing that

the son of another member of their clan. A hereditary jeweller was known as a shınjır zerger – literally 'jeweller chain'.

Zergers belonged to craft guilds which had masters (usta) and apprentices (sha'kirt). They believed they were

protected by a spirit (pir) called Ha'zireti Dawit. They followed a strict set of regulations known as risa'le. Innovation

was discouraged – the apprentice was merely supposed to copy the work of the master. An apprentice could only become a master after many

years of training – sometimes up to ten years. When he was judged to be ready he received the blessing (pa'tiya) of the master in

front of the members of the guild.

The hereditary nature of this craft can be seen from the following example:-

| Arıs | Division | U'lken Urıw | Urıw | Tiıre | Number |

| On To'rt Urıw | Qıtay | Beksıyıq | Zerger | 2 | |

| On To'rt Urıw | Qıtay | Qazayaqlı | Unknown | 1 | |

| On To'rt Urıw | Qıtay | Qırıq | Unknown | 1 | |

| On To'rt Urıw | Qıtay | Aralbay | Unknown | 2 | |

| On To'rt Urıw | Qıtay | Bessarı | Unknown | 3 | |

| On To'rt Urıw | Qıpshaq | Yabı | No sub-groups | 5 | |

| On To'rt Urıw | Qıpshaq | Yestek | Unknown | 1 | |

| On To'rt Urıw | Man'g'ıt Qaratay | Qarasıyraq | No sub-groups | 1 | |

| On To'rt Urıw | Man'g'ıt Qaratay | Mamiqshı | Unknown | 1 | |

| On To'rt Urıw | Man'g'ıt | Unknown | Unknown | 2 | |

| On To'rt Urıw | Keneges | No'kis | Altınpıshaq | 1 | |

| Qon'ırat | Shu'llik | Qıyat | Balg'alı | Unknown | 1 |

| Qon'ırat | Shu'llik | Qıyat | Taraqlı | Qarjawbaras | 3 |

| Qon'ırat | Shu'llik | Qıyat | Unknown | Unknown | 1 |

| Qon'ırat | Shu'llik | Mu'yten | Samat | Unknown | 3 |

| Qon'ırat | Shu'llik | Mu'yten | Ken'tanaw | Unknown | 2 |

| Qon'ırat | Shu'llik | Mu'yten | Abız | No sub-groups | 2 |

| Qon'ırat | Shu'llik | Qaramoyın | Unknown | Unknown | 1 |

| Qon'ırat | Shu'llik | Qa'ndekli | Kiyikshi | No sub-groups | 1 |

| Qon'ırat | Shu'llik | Qoldawlı | Qalqaman | No sub-groups | 1 |

| Qon'ırat | Jawıng'ır | Teristamg'alı | Unknown | Unknown | 3 |

| Qon'ırat | Jawıng'ır | Baqanlı-Sha'wjeyli | No sub-groups | No sub-groups | 5 |

| Qon'ırat | Jawıng'ır | Uyg'ır | Unknown | Unknown | 6 |

| No. | Name | Date | Clan | Region | Items |

| 1 | Ablaysan' zerger | 1871-1931 or 1855-1920 | Moynaq region, Go'nedar'ya, Aq qala, Qara qala, Shege, Tallıq, Shımbay | Jumalaq tu'yme - 5 examples KP845-849. Shartu'yme - 2 examples KP299-300 | |

| 2 | Aleke zerger. Father of Arzımbet (8). Grandfather of Seytmurat (64) | Middle of the 19th century | Mu'yten Samat | Taxta Ko'pir, Terbenbes | |

| 3 | Allambergen zerger | Taxta Ko'pir region | Ha'ykel, tu'yme, ju'zik etc. | ||

| 4 | Amanbek zerger. Senior brother of Kamal (32) | Died between 1927-1929 | Beksıyıq clan, Zerger tiıre | Kegeyli region, Xalqabad sovxoz | Sa'wkele, to'belik, 12 qaslı ha'ykel. O'n'irmonshaq KP1912. |

| 5 | A'met zerger Nasırov. Son of Nasır (39). Great grandson of Tu'kibay (71) | Baqanlı | Taxta Ko'pir, sovxoz "Soviet Uzbekistan" | See image of him with o'n'irmonshaq above. His tools were preserved. | |

| 6 | Arıq zerger | Qazayaqlı | Kunya Urgench in Turkmenistan | The museum does not have his works | |

| 7 | Arzek zerger. Son of Xojaniyaz (76). Grandson of Espambet (23). Great grandson of Ko'shek (36). 4 generations of zergers. Senior brother of Qallıqoraz (50) | 1860-1935 | Qıpshaq tribe, Yabı clan | Aq Darya, Porlıtaw, Shege | Degment belbew, ala qayıs, ka'ma'r, ha'ykel, ju'zik etc. Hay'kels KP1741 and KP1227, Ka'ma'r KP306 and 369 |

| 8* | Arzımbet zerger. Son of Aleke (2). Father of Seymurat (64) | 1856-1936 | Mu'yten Samat | Terbenbes, Qazaqdarya | Sa'wkele, to'belik, shartu'yme, bilezik, ju'zik, jalpaq tu'yme, jumalaq tu'yme - 12 - KP1992-1997, 1609-1614, sırg'a KP1928, 1984-85, 1991, o'n'irmonshaq - 2 - KP1989-199, 192, ha'ykel KP1988, qız ha'ykel KP1983. |

| 9 | Axımbet zerger. Father of Eshmurat (22) and Jaqsımurat (29) | Middle of the 19th century | Bessarı | Shımbay, Kegeyli | |

| 10 | Aybergen zerger | Xojeli region | Sa'wkele, ha'ykel, tu'yme. A'rebek KP1918 | ||

| 11 | Aytmurat | Moynaq region | Tumarsha KP301-303 | ||

| 12 | Bazarbay zerger Eshanov. Molla Asqar was his teacher | 1869-1917 | Ancestors moved from Qon'ırat clan to Qıyat clan but he was Aral Uzbek | Native of Tashauz. Worked in Xalqabad, No'kis | Made a wide variety of Qaraqalpaq items including sa'wkele |

| 13 | Bayımbet zerger. He was related to Tu'kibay (71) | ||||

| 14 | Bo'lekbay - blacksmith. Son of Ιrza - blacksmith (27) | Died in 1950 | Qarao'zek region, Moscow sovxoz | ||

| 15 | Da'wletniyaz zerger | 1898-1948 | Kegeyli, Xalqabad | ||

| 16 | Dosnazar Serekeev | Mu'yten Ken'tanaw | Jartapsan | Tu'yme No. 340 | |

| 17 | Eleke zerger | Kegeyli, Bozataw | |||

| 18 | Elman zerger | Kegeyli | |||

| 19 | Elmurat zerger. Apprenticed to Qaliyla (48) | Bozataw | |||

| 20 | Erejep zerger | 1879-1939 | Baqanlı | Qon'ırat | |

| 21 | Ernazar zerger | Qoldawlı, Qalqaman | Zair, Kunya Qarao'zek | Ha'ykel KP2080, jumalaq tu'yme KP2086-2087 | |

| 22 | Eshmurat zerger. Son of Axımbet (9). Teacher of his junior brother Jaqsımurat (29) | Bessarı | Kegeyli, Xalqabad | ||

| 23 | Espambet zerger. Son of Ko'shek (36). Father of Xojaniyaz (76). Grandfather of Arzek (7) | 19th century | Qıpshaq, Yabı | Aq Darya, Moynaq region | |

| 24 | Ha'kimbet zerger | Mu'yten Samat | Taxta Ko'pir region, shores of Esimo'zek | ||

| 25 | Ha'kim zerger | Worked at the beginning of the 20th century | No'kis, Altınpıshaq | Kegeyli region, Engels sovxoz | |

| 26 | Ibrayım zerger | Taxta Ko'pir | |||

| 27 | Ιrza - blacksmith. Father of Bo'lekbay (14) | 2nd half of the 19th century | His ancestors were blacksmiths from Turkestan | Qarao'zek region, from the village of blacksmiths that was renamed Moscow sovxoz | Cauldrons, pitchers, cast iron arrows. Also sold them to Kazakhstan |

| 28 | Ismail blacksmith | Born in 1912 | Qarao'zek | ||

| 29 | Jaqsımurat zerger. Son of Axımbet (9). Apprentice to his elder brother Eshmurat (22) | Bessarı | Kegeyli | ||

| 30 | Jollıbek zerger | Died in the 1930s | Kegeyli, Shımbay, Taxta Ko'pir | Ha'ykel KP1236. Specialized in ornamentation of doors and wooden parts | |

| 31 | Juman zerger | Qıyat Baqanlı. This may be incorrect as Baqanlı is part of the Jawing'ır division and Qıyat is part of the Shu'llik | Qon'ırat | ||

| 32 | Kamal zerger. Junior brother of Amanbek (4) | Beksıyıq clan, Zerger tiıre | Kegeyli then Xalqabad | ||

| 33 | Kemal zerger | Worked in the 1930s | Qıtay Qırıq | Qarao'zek, invited to work in Kegeyli | |

| 34 | Kemal zerger | Qazaq nationality | Kegeyli | Ju'zik KP1537, bilezik KP1547, atanaq sırg'a No. 1549, giltshalg'ısh No. 1535, ha'ykel No. 1543, sırg'a Nos. 2142-2143. | |

| 35 | Ko'beysin zerger | Qarao'zek, Ko'ko'zek | A'rebek, sırg'a, ju'zik etc. | ||

| 36 | Ko'shek zerger. Father of Espambet (23). Grandfather of Xojaniyaz (76). Great-grandfather of Arzek (7) | Lived at approximately the end of the 18th century | Qıpshaq, Yabı | Aq Darya, Moynaq region | |

| 37 | Medetbay zerger | Qazaq | Qon'ırat region | Tumar KP504, jumalaq tu'yme KP505-508 | |

| 38 | Miyrixan zerger | Qaramoyın | Qarao'zek region, Ko'k ko'l | Jumalaq tu'yme KP2101 | |

| 39 | Nasır (Nasırulla) zerger. Father of A'met (5). Grandson of Tu'kibay (71). | End of the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century | Baqanlı | Taxta Ko'pir | |

| 40 | Nızan zerger. Son of Abdika'rim | Qıyat | Qon'ırat region | Ha'ykel, jumalaq tu'yme, halqaplı sırg'a, bilezik | |

| 41 | Nuraddin zerger | Leninabad region, Khorezm sovxoz | |||

| 42 | Nurbaev Bazarbay, coppersmith | Born 1881 | Man'g'ıt | Shımbay | |

| 43 | Nurımbet zerger. Son of Aytımbet | Born 1905 | Aralbay | Xojeli region, Engels kolxoz | Sırg'a, bilezik. Materials used were silver and carnelian. Techniques were filigree and granulation. |

| 44 | Omar zerger | 1878-1928 | Sha'wjeyli | Qarao'zek region, Kalinin sovxoz | Jalpaq tu'yme KP1314, 1317, o'n'irmonshaq KP1313, 1331, 1491, shartu'yme KP1311, jumalaq tu'yme KP1318, 1325, giltshalg'ısh KP1327, ha'ykel KP1309-1310 |

| 45 | Oraz zerger. Son of Qurbanbay (56) | Mu'yten, Abız | Jumalaq tu'yme KP2051-2053 acquired in Qazaqdarya | ||

| 46* | Orazımbet zerger. Friend of Turımbet (73). Father of Seytmurat (64) | Uyg'ır | Kegeyli region, Porlıtaw | ||

| 47 | Qa'dirimbet zerger | Uyg'ır | Moynaq region, Tilewbayo'zek | ||

| 48 | Qaliyla zerger. Teacher of Elmurat zerger (19) | Qa'ndekli Kiyikshi | Leninabad rayon, (Sverdlov sovxoz). originally from Bozataw rayon, Erkindar'ya | Ha'ykel, o'n'irmonshaq | |

| 49 | Qaliyla zerger | Taxta Ko'pir region | |||

| 50 | Qallıqoraz. Junior brother of Arzek (7) | 1890-1945 | Qıpshaq, Yabı | Porlıtaw, Shege | |

| 51 | Qalmurat, coppersmith. Son of Ja'leke | 1890-1957 | Moynaq region, Aq Darya, Shımbay | ||

| 52 | Qaniyaz zerger | 1815-1904 | Qıyat Balg'alı | Shomanay, Qon'ırat | Ha'ykel KP1164 |

| 53 | Qon'ıratbay zerger | Man'g'ıt, Mamıqshı | Kegeyli region, Shartay-qala | ||

| 54 | Qoraz zerger. Son of Tilewbay (68). Father of Xudaybergen (79) | 1848-1919 | Uyg'ır | Porlıtaw, Shortanbay | Several examples of his tools and moulds are shown on this webpage |

| 55 | Qosbergen zerger | Kegeyli region | |||

| 56 | Qurbanbay zerger. Father of Oraz (45) | Mu'yten Abız | |||

| 57 | Qurbanbay blacksmith. Son of Ιrza (27) | Died in 1950 | Qarao'zek region | ||

| 58 | Raman zerger | Shımbay region | |||

| 59 | Sapar zerger | Moynaq region, Shege, Porlıtaw | Made a sa'wkele for Qaniyaz bay | ||

| 60 | Saparlaq zerger | Kegeyli region | O'n'irmonshaq KP1140, jalpaq tu'yme KP1444 | ||

| 61 | Sayıp zerger | 1874-1928 | Qarasıraq | Kegeyli region, Xalqabad | |

| 62 | Sereke zerger | End of the 19th century | Mu'yten Ken'tanaw | Moynaq region, Qazaqdarya | |

| 63 | Seydabılla zerger | Teristamg'alı | Moynaq region, Aq Darya | ||

| 64 | Seytmurat. Son of either Arzımbet (8) or Orazımbet (46). Grandson of Aleke (2) | 1885-1950 | Uyg'ır Dombazaq, Qazaqdarya, Qusxanataw | ||

| 65 | Shawdırbay zerger | 1852-1922 | Qıyat, Qarjawbaras. (First information given to Allamuratov said Ashamaylı, Sarı Qarag'an) | Moynaq Qon'ırat region, Bozataw, Sorko'l | Ha'ykel KP819, ala qayıs ju'wen KP484, qız ha'ykel KP807, 811, jumalaq tu'yme KP308-309, 816-818, jalpaq tu'yme KP812-813, shartu'yme KP808-809, o'n'irmonshaq KP820 |

| 66 | Smetulla zerger | Teristamg'alı | Moynaq region | Halqaplı sırg'a KP368, sobıqlı sırg'a KP377, ayshıq, bilezik, tis shuqlag'ısh | |

| 67 | Sultamurat zerger | Teristamg'alı | Moynaq region, Aq Darya | Ha'ykel, jumalaq tu'yme, ilgek tu'yme, halqaplı sırg'a, ayshıq, a'rebek, tumar | |

| 68 | Tilewbay zerger. Father of Qoraz (54). Grandfather of Xudaybergen (79) | Uyg'ır | Shortanbay, Porlıtaw | ||

| 69 | To're zerger | Died in 1936 | Uyg'ır | Kegeyli region, Engels sovxoz. Moved here from Porlıtaw | O'n'irmonshaq KP1568, bilezik KP1500-1501 |

| 70 | To'remurat zerger | Qıtay, Aralbay | Qon'ırat region, Qanlıko'l | Bilezik KP1913-1914, degment belbew KP362-363 | |

| 71 | Tu'kibay. Great grandfather of A'met (5). Granfather of Nasır (39) | Assume Baqanlı as that was the clan of his forefathers | Taxta Ko'pir | ||

| 72 | Turdımurat zerger. Son of Xojaniyaz (77) | Qıyat, Qarjawbaras | Qon'ırat region, Ilmeko'l | ||

| 73 | Turımbet zerger Shraziev. Xojamurat (75) was his teacher | Born in 1870 | Estek | Kegeyli region, Porlıtaw | Ha'ykel, degment belbew, ala qayıs ju'wen, o'n'irmonshaq, halqaplı sırg'a, a'rebek, tu'yme, bilezik |

| 74 | Uzaqbergen zerger | Bozataw region | Ha'ykel KP1365 | ||

| 75 | Xojamurat zerger. Taught Turımbet (73) | Moynaq region | |||

| 76 | Xojaniyaz. Grandson of Ko'shek (36). Son of Espambet (23). Father of Arzek (7) | 19th century | Qıpshaq, Yabı | Aq Darya, Moynaq region | |

| 77 | Xojaniyaz zerger. Father of Turdımurat (72) | Qıyat, Qarjawbaras | Qon'ırat region, Sorko'l, Ilmeko'l, Sırlıtas | ||

| 78 | Xojaniyaz zerger | 1830-1910 | Man'g'ıt | Qarajar, Sırlıtas, Taxtaqayır | Ha'ykel, o'n'irmonshaq |

| 79 | Xudaybergen zerger. Son of Qoraz (54). Grandson of Tilewbay (68) | 1885-1969 | Uyg'ır | Kegeyli region, Shortanbay - then moved to Shomanay | Sa'wkele, to'belik, ha'ykel, shartu'yme, jalpaq tu'yme, gilt shalg'ısh, o'n'irmonshaq, bilezik, ju'zik |

|

We can see that a mould similar to the one in the top right corner of the following illustration was used to make some of the pendants on this

ha'ykel.

|

Another item recovered from the former workshop of Qoraz Tilewbayev was the casting for a quyma bilezik bracelet:

|

The casting is very similar to the following pair of finished quyma bilezik:

|

O'temisov was able to compile a complete list of the equipment used by a zerger from information given by Nurımbet Arzımbetov

from Xojeli and from the examination of a workshop used by Xudaybergen (which contained the tools of his grandfather Tilewbay shown above), which

was still preserved in the Shomanay region.

| Qaraqalpaq name | Tool |

| To's | Anvil |

| Sho'kkish | Different hammers |

| Tu'tik or nay | Wooden pipe with metal tip used in soldering |

| Ko'rik | Bellows made from goatskin |

| Ko'riktin' oshaqı | Small clay circular home-made furnace |

| Qa'lip or u'lgi | Different metal and wooden moulds |

| U'sh qırlı yegew | Triangular files |

| To'rt qırlı yegew | Four sided files |

| Jalpaq yegew | Flat files |

| Qashaw | Type of chisel |

| Qısqısh | Tongs used in forging |

| Iskenje | Vices |

| Sımtarash | Metallic plates with holes of various sizes for drawing silver wire |

| Teskish | Punches |

| Keskish | Type of chisel |

| Temir kesew | Poker |

| Da'neker | Soldering iron |

| Kepkir | Crucible |

| Qayshı | Scissors for cutting thin metal and wire |

| Izey qa'lem | Bronze/iron chisels with pattern on the end used for applying the pattern onto soft metal |

| Ta'rezi | Weights to weigh the metal or stones |

|

This page was first published on 6 April 2009. It was last updated on 5 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2018. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |