The Qaraqalpaq Sa'wkele - Part 1

|

The Qaraqalpaq Sa'wkele - Part 1

|

|

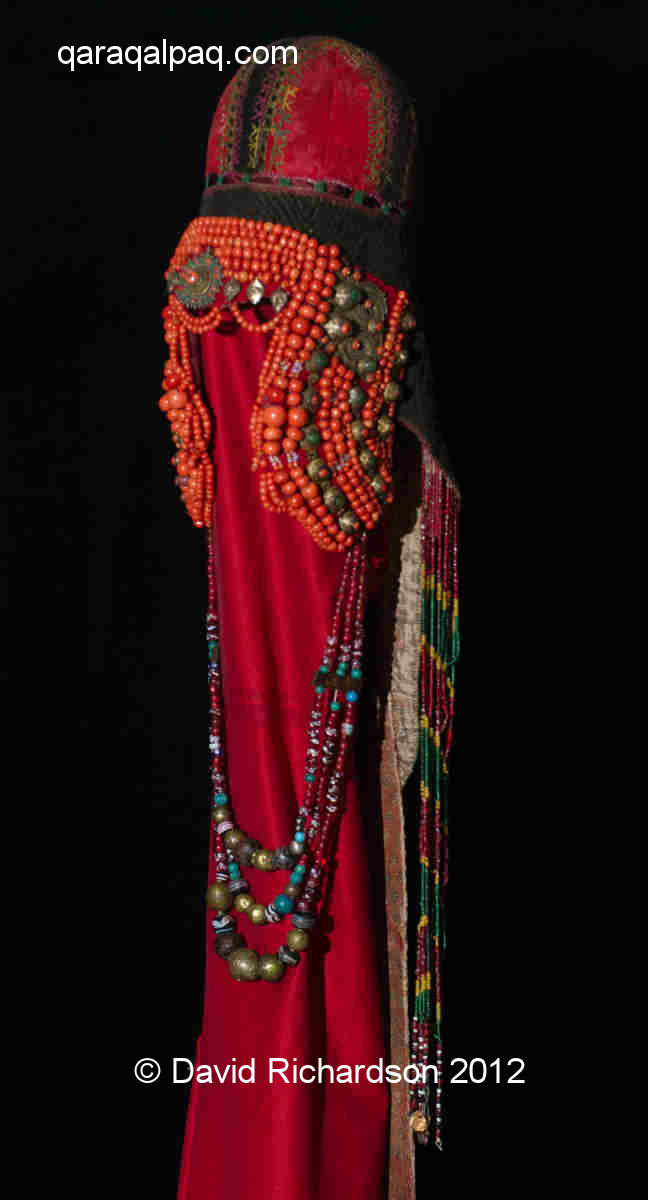

ContentsPart 1The Sa'wkeleStructure and Design Materials Ceremonial Use Part 2Sa'wkeles in MuseumsThe To'belik Qazaq, Kyrgyz, Uzbek, and Turkmen Headdresses Other Central Eurasian Headdresses Part 3Mythology of the Sa'wkeleOrigin of the Sa'wkele Conclusions Pronunciation of Qaraqalpaq Terms References The Sa'wkeleThe Qaraqalpaq sa'wkele is an elaborate ceremonial headdress embellished with corals and semi-precious stones, once worn by the daughters of the wealthy tribal aristocracy during their marriage ceremonies in the 19th century. Their use died out in the early part of the 20th century. Today sa'wkeles are extremely rare and no more than seven exist in the museums of No'kis and Saint Petersburg.

The restored Qaraqalpaq sa'wkele from the Zayır region of the Aral delta

|

|

The Qaraqalpaq (and Qazaq) spelling of the name for this headdress is сәўкеле (,em>sa'wkele,/em>, while

the Russian is саукеле. Consequently Russian academics refer to the saukele. M. S. Andreev

argued that the word sa'wkele has a compound formation and is not Turkic but of ancient Iranian origin, formed from the word

for king, shah, and for hat or head, kuloh or kelle. He claimed that in a Turkic Qipchaq language such as

Qaraqalpaq or Qazaq this changed phonetically into shevkele or sa'wkele, depending on whether it was pronounced

with a "sh" or an "s". The word kulokh has been used across Central Asia in relation to both male and female headwear since

the Middle Ages.

Alternative interpretations are based on the word sa'w, which in Turkic can mean health and happiness and in Qazaq can mean

solar or beautiful. In Qaraqalpaq the word sa'wle means ray, beam, or glow.

There is no scientific evidence to indicate the true etymology of the word.

Structure and Design

A typical sa'wkele is constructed from three main components:

|

|

The paddle-shaped halaqa plait cover is attached to the back of the tumaq by its upper edge. This is

made of qara ushıga with a qızıl ushıga outer border. It is decorated with simple

embroidered motifs using silk threads and is lined with block-printed cotton bo'z. The word halaqa normally refers to the

loose ends of a turban that hang down the back. It is made from four long and narrow strips of asmyie embroidery arranged in parallel

and sewn together side by side except towards the very bottom, where they are allowed to separate like a feathered tail. Indeed it is frequently

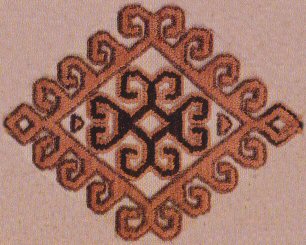

compared to a folded peacock's tail. The strips are decorated with floral patterns executed in basma technique in which coloured silk

threads are couched at right angles to produce a ribbed effect, frequently seen in Uzbek suzanis.

|

Strings of small beads hang down from the rear of the black netting, on either side of the halaqa. These are arranged in coloured

sections of red (the same shade as pomegranate seeds), green, and yellow and in places are linked horizontally so that they hang together as

one.

|

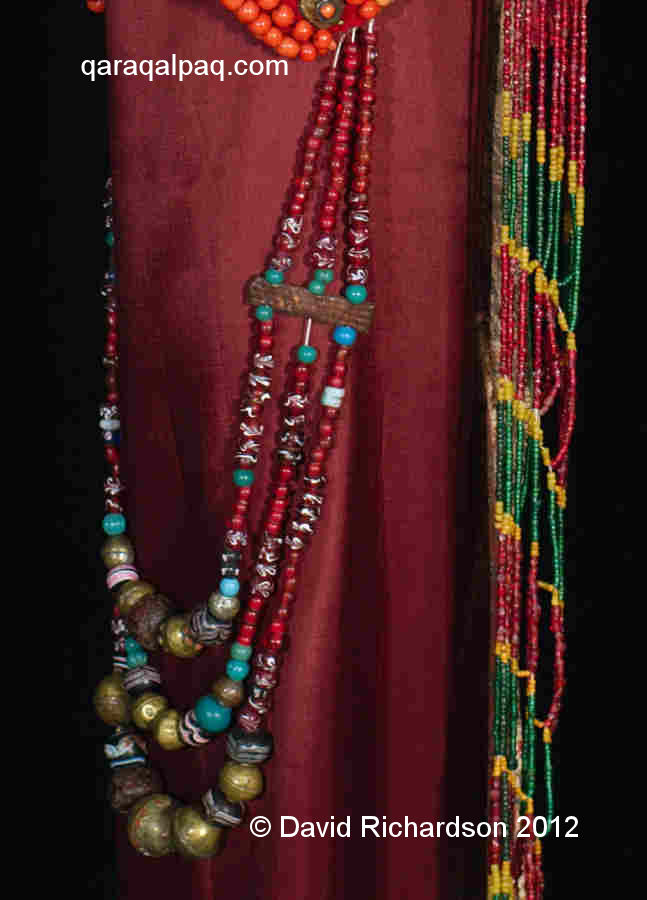

A more prominent cluster, composed of three separate strings of beads of increasing length, is attached to the bottom of each earguard.

It is intended to hang like a necklace across the breast. These strings are called boydası - a boyda being a rope for

tying a camel. The beads vary in nature and size, with small pomegranate-coloured beads, decorated glass beads, beads of paste and of

turquoise stone, a few beads of resin, and some larger beads of hollow bronze.

Materials

|

As the 19th century progressed private Russian companies increasingly industrialized. The best textile machinery at that time was made in

England, but for protectionist reasons its export was proscribed until 1842. From the 1840s onwards the number of Russian textile mills

expanded rapidly, many spinning, weaving, and printing cotton but a smaller number weaving and fulling wool to make broadcloth or sukno,

although this was of inferior quality to English cloth. Not only English machinery but also English managers and technicians were brought to

Moscow to equip the new factories and to train their employees.

Russian manufactures were imported into Khorezm by regular caravans, numbering from one to two thousand camels, operating out of Orenburg

and Astrakhan, usually travelling via the Syr Darya. However when James Abbott visited Khiva in 1839 it was a time of increased hostility

between Russia and Khiva so goods had to be imported via Bukhara. He noted that articles imported from Orenburg and Astrakhan at that time

included both broadcloth and cotton cloth. Vambery gives figures provided by the British Embassy in Saint Petersburg indicating that some

£26,000 of Russian woollen manufactures were imported into Khiva between 1840 and 1850. Imports of woollen goods jumped fourfold between

the 1850s and the 1860s but varied significantly from year to year. During the 1860s quantities were generally minimal but exceeded

80,000 roubles in the two years of 1865 and 1866.

Even so Russian merchants and manufacturers remained concerned about the increasing penetration of English goods from Persia and Afghanistan.

In 1850 the manufacturer Pichugin wrote to the Russian authorities noting that England would soon outstrip Russia in its trade with Central

Asia and was engaging in Bukhara and Khiva in order to shield its Indian possessions from Russia. In 1869 the Orenburg authorities barred

the import of European goods, giving Russian producers exclusive access to the markets of Turkestan.

|

Following the Russian conquest of Khiva in 1873 Russian merchants established trading stations in New Urgench and imports from Russia began

to become more regular. Spalding noted that cloth and cotton prints remained the chief articles of import from Russia in 1874. The completion

of the Transcaspian railway in the 1890s meant that goods could now arrive from Russia via Chardzou or by ferry from Aralsk. Imports of

Russian sukno amounted to 15,000 roubles in 1894 and 17,600 roubles in 1899. Between 1907 and 1912 textiles accounted for 35 to

40% of the value of all Russian imports into Khiva.

Qaraqalpaqs regarded ushıga as a prestigious textile, which for them was extremely expensive. As a result of days of machine

hammering the surface of broadcloth is closely felted, concealing the weave. Cutting produces a smooth and even finish, quite unlike any handwoven

textile and ideally suited for embroidering. Whereas coarse bo'z was suited for geometric cross-stitch embroidery, broadcloth

was perfect for chain-stitch. Its increasing availability from the 19th to the 20th century led to a change in Qaraqalpaq fashion, with chain-stitch

embroidery becoming ever more popular.

|

Coral is foreign to Central Asia and must have been imported from the Mediterranean, India, or China, Mediterranean coral being the most sought

after. In the Mediterranean coral is found along the coasts of Algeria and Tunisia, in Spain, France, Corsica, Sardinia, and Sicily, and in

Turkey and the Red Sea. The Persian Hudûd al-Âlam, written in 982, recorded that there was no place like Tabarqa in the Maghreb for coral,

with its offshore coastal coral banks, although it was also imported from Hindustan. In 1222 the Chinese delegation accompanying the Taoist monk

K'iu Ch'ang Ch'un purchased fifty coral branches from Mongol soldiers who were returning from "the Muslim territories" to Mongolia. The Chinese

were travelling back to Samarkand from a meeting with Chinggis Khan in the foothills of the Hindu Kush. Marco Polo found that coral was especially

highly valued in land-locked Kashmir.

Coral also occurs in the coastal waters of India and Sri Lanka, China, and Malaysia. When Ole Oulfsen was in Bukhara in the late 19th century

he found that coral or mardyan was greatly valued for female adornment. It was brought overland from China and "magnificent specimens

both in white and in red" could be found on all the bazaars.

|

In her study of 19th century Bukhara, Olga Sukhareva described the various craft districts of the city, known as guzars.

Guzar number 159 was known as the "alaqa-bandon" district, and was probably the location of workshops for the production

of alaqa. They were used by wealthy female Bukharan Uzbeks as plait covers, and some can be found today in museum collections

(see for example page 286 in Johannes Kalter and Margareta Pavaloi, Uzbekistan, Heirs to the Silk Road, Thames and Hudson, London, 1997).

Ceremonial Use

The sa'wkele fulfilled three main functions for the Qaraqalpaq bride:

|

Ethnographers from the Khorezm Expedition also studied the clothing of the Uzbeks who lived in the Aral delta during the period 1946-1948.

Elderly Uzbek women confirmed that in the old times they too, just like the Qaraqalpaqs and Qazaqs, had the sa'wkele and the

to'belik-like kasava headdress, although by then they were no longer in use.

Nina Lobacheva has summarized some of the responses from Qaraqalpaq people who claimed that the sa'wkele was worn above the

kiymeshek. In Shımbay region it was claimed that the kiymeshek was worn below both the sa'wkele and the

to'belik. In Kegeyli region they noted that the sa'wkele and the kiymeshek were put on for the first time during

the day when they transported the bride into the house of her fiancé. However, in 1956 one of the Kegeyli informants who was born in 1900

described this in more detail. She remembered that women still wore the sa'wkele during holiday festivities when she was 15 to 16

years old, in other words around 1915 to 1916. Sa'wkeles were reserved for the daughters of the rich and were financed by their

fathers. The bride was first dressed in the kiymeshek and sa'wkele on the day of the wedding, after she had been brought

into the house of her fiancé.

|

In the Qarao'zek region however the sa'wkele was first put on after the bride had descended from her arba near the house

of her fiancé. In the Qonırat region they reported that the bride was dressed in the sa'wkele by her tutor or jen'ge

(the wife of an elder brother or uncle) at her own home on the day of the wedding after she was placed in her arba to travel to the

house of her fiancé. She wore a kiymeshek under the sa'wkele but not a to'belik. The bride wore the sa'wkele

after her wedding for holidays and feasts. In Taxta Ko'pir region they claimed that it was not necessary to wear a kiymeshek under

the sa'wkele at all. Mu'yten-Ken'tanaw people from Tasbesqum Island confirmed that they tied a small headscarf under the sa'wkele

and then tied a turban-shaped silk scarf or tu'rme above it, covering the entire head. Mu'yten-Teli people from Qaraboylı Island

and Qıyat-Ashamaylı from Moynaq said that the tu'rme was wound lopsidedly so that the sa'wkele was mainly visible

from the right side, only the metallic platelets lining the forehead being visible from the front.

Lobacheva realized that by the middle of the 20th century elderly people had forgotten a great deal about their traditional customs. She came

to the conclusion that on the day of the wedding party the bride was dressed in the sa'wkele in her own house by a woman from her side

of the family and was dressed in the kiymeshek in the house of her fiancé by a woman appointed from his side of the family, known as the

bride's proxy mother or murındıq ene.

At the beginning of the 20th century the trousseau of an aristocratic bride consisted of a small headscarf, a kiymeshek, the

sa'wkele, a tu'rme, and finally a jegde to cover her head (either a pashshayı jegde or a jipek jegde).

At the same time the sa'wkele and the kiymeshek had become part of the holiday costume of the newly-wedded bride. During the

u'yleniw-toy, the main wedding party, the bride would initially be introduced to the families and their guests in her complete

costume, her face concealed by a white cloth or shawl. The face opening ceremony or bet-ashar would then be conducted with the assistance

of a storyteller or baxsı at the end of which the face of the bride was finally revealed to the crowd.

|

The sa'wkele would have been commissioned from a local respected jeweller by a very wealthy father well in advance of the marriage

of his eldest daughter. Some reports suggest the sa'wkele became an important part of the bride's dowry and was passed from mother

to daughter. However others suggest it was returned to the father for use in further family weddings.

After the wedding the newly married bride only wore the sa'wkele for important ceremonial occasions, up to the birth of her first

child. However other informants have said that the interval was longer, extending through the first five years of marriage.

Clearly in some regions the sa'wkele was once used in combination with the to'belik, while in others the to'belik

may have been used as a headdress for unmarried girls. Xojamet Esbergenov believes that to'beliks may have been worn by girls

during the period in which they were engaged to be married, thus communicating their non-single status. This likelihood of a dual purpose

is reinforced by the nature of the two existing to'beliks themselves. The example from the Hermitage is displayed encasing the

tumaq of a sa'wkele while that in the Savitsky Museum seems to be shallower and must be a separate self-contained headdress

since it cannot be physically fitted over the top of a sa'wkele.

Return to top of page

Go to Part 2

Go to Part 3

|

This page was first published on 12 September 2006. It was last updated on 25 February 2012. © David and Sue Richardson 2005 - 2018. Unless stated otherwise, all of the material on this website is the copyright of David and Sue Richardson. |